“When life throws you a lemon, throw it back” – a slogan written by American writer and lecturer Dale Carnegie in his bestseller book “How to Stop Worrying and Start Living” from 1948. Perhaps there is no better display of this philosophy than the life story of the German painter Helmut Hermann Krommer (1891-1973).

Helmut Krommer is an ethnic German born in the Czech city of Opava (German name Troppau) in the Moravia province. Under de influence of his father, who was a well know lawyer, Krommer studied law, but his passion elsewhere: in fine art. In 1911, he decided to follow his heart, he quit studying law and move to the studies of art history in Vienna, and later in 1913 he started studying fine art at the prestigious Vienna Art Academy.

Then, life started to test his strength. The World War One erupted and Krommer was mobilized and sent to the western front where in 1914 he was heavily wounded in his arm. After long recovery, in 1915 he was mobilized again and sent to Macedonia and Albania. He stayed there with the German army until 1917 when he got sick from malaria and sent for recovery back to Germany. He survived malaria, only to get sick from Spanish flu in 1918. His friends and family started to mourn him, but he miraculously healed from the flu as well.

After this turbulent period, life takes him to calmer waters. Krommer goes back to studying art at the Baden State Art Schoon in Karlsruhe. Upon graduation, he moves to Berlin where he lives as a freelance artist. He manages to get scholarship for a study trip in 1924 and he visits Yugoslavia and Greece again. He was especially impressed by the Yugoslav mixture of byzantine and oriental art heritage and its folklore, which influences his artistic style. It seems that the worst in his life was behind him. But not for long.

In January 1933, Adolf Hitler’s National-Socialistic party took the government and Hitler became a prime minister. He immediately began with the elimination of his political opponents. The Nazi threat-squads are marching on the streets of Berlin and demolishing the houses, flats, and stores of the Jewish citizens and critics of the Nazi party. Helmut Krommer is a member of the opposition social-democrats and he also takes part in the editing of their newspaper “Vorwärts”.

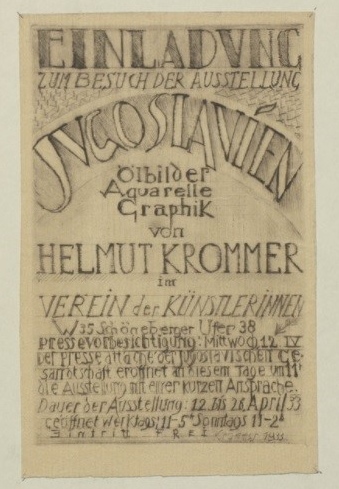

In April 1933, Krommer distanced himself from politics and focused himself in setting up the exhibition of his Yugoslav paintings, watercolors, and graphics under the patronage of the Embassy of Yugoslavia in Berlin. The exhibition opened on 26th of April 1933 and got positive critics from the Berlin art audience and media. This positive publicity irritated the Nazis. On the night of 20th April 1933, the Nazis stormed and demolished his house and threaten to kill him and his wife, who was Jewish. The morning after, on May 1st 1933, Helmut Krommer, his wife and his two daughters took few bags and run away to Prague. They never returned back to Germany.

The exhibition ended in May, but there was no one to collect the paintings. The Yugoslav embassy took fiver paintings and the rest of the wart works vanished without a trace. His Macedonian works of art created during his stay in Macedonia in 1916-17 and later in 1924 are probably part of this batch of a lost art.

Krommer lives with his family in Prague. But life challenges him again. On 15th March 1939, Hitler annexes Czechoslovakia to Germany. On that very same day when the Nazi troops are marching into Prague, Krommer flees again, this time with assistance from the Embassy of Yugoslavia, he and his family first flee to Yugoslavia, and then to United Kingdome.

Helmut Krommer spends the war in Guildford near London. It is not easy to be a German living in a country that is attached by Germany. His good sense of humor keeps his morale high. To sound less German, He calls himself and signs his works with the name „Lord Cromer-Peniless of Guildford“.

The war is over and Germany in ruins. Despite the fact that he is born in Czechoslovakia, as an ethnic German he is not welcomed back.

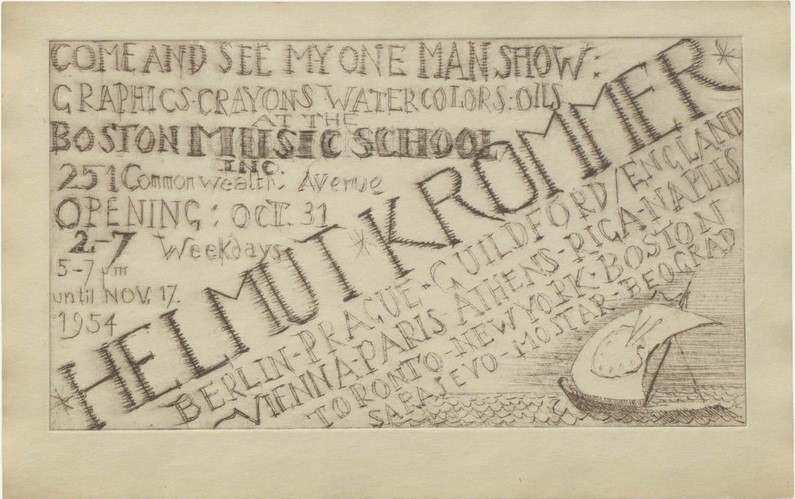

He picks his next destination – Boston, USA, where his daughter Anna already lives for some time. Krommer lives in Boston until the end of his life in 1973. He still paints and makes graphics, and he works as an illustrator and freelance journalist for local newspapers. In the 1950s, he organizes another exhibition in Boston, and some of his Yugoslavian works are presented there too, but it is not clear if any Macedonian work of art survived the trip to USA and was exhibited there

In the past 15 years I have unsuccessfully searched for Krommer’s work of art with Macedonian subjects. I hope that I will find at least a photograph of those art works , somewhere on internet. It is almost impossible to trace the lost art from his 1933 Berlin exhibition.

Each time I lose hope, some new spark of hope appears. Recently I have been contacted by Mr Zoran Andonov, a Macedonian journalist who has written an interesting story on the Macedonian news web site sdk.mk about a colorful character called Stole Zilecki, whom Helmut Krommer met in Macedonia and wrote a story in an American newspaper in the 1920s. This new lead has sparked by interest again and I have restarted the internet search queries in hope for finding a new information on Krommer. I am confident that I’ll be lucky and one day I’ll find a Macedonian work of art made by him. As John Lennon from The Beatles said, “Everything will be OK at the end, and if it is not OK, then it is not the end.”

Sources of information and photos:

- https://kuenste-im-exil.de/KIE/Content/DE/Personen/krommer-helmut.html

- http://www.digiporta.net/pdf/GNM/Krommer_253194250.pdf

- https://kuenste-im-exil.de/KIE/Content/EN/Persons/krommer-helmut-en.html

- https://kuenste-im-exil.de//KIE/Content/EN/Objects/krommer-ausstellungberlin-radierung-en.html?single=1

- https://sdk.mk/index.php/magazin/za-stole-zhilechki-skitnik-od-leshochkiot-manastir-koj-govorel-6-jazitsi-pishuvale-vesnitsite-vo-amerika-vo-pochetokot-na-20-vek/