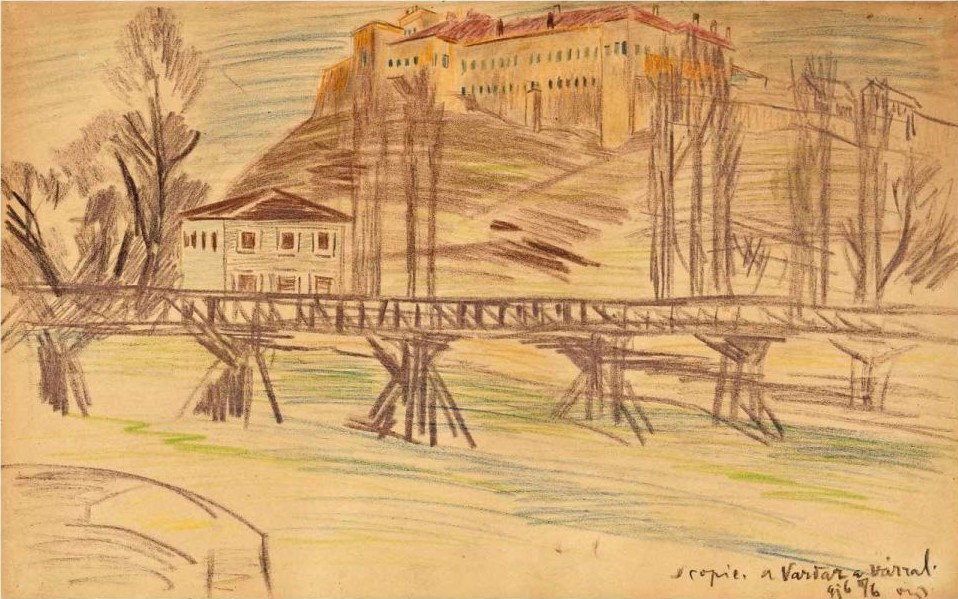

It is May 14, 2019. I woke up with a new message from my “Macedonian art” internet search queries. The Hungarian auction house BÁV Zrt from Budapest is offering a large pastel drawing entitled “Scopie, Vardar with castle 916 II/6” from the Hungarian painter János Vaszary (Kaposvár, 1867 – Budapest, 1939) on their May 15th auction.

“Hungarian? They don’t come that often” – I thought. My Lexicon had only a few entries of Hungarian artist that visited Macedonia with very scarce details: Bela Kron (only information that he was in the army in WW1 in Macedonia), Gustav Miklos (1888-1967) (who was with French army in Thessaloniki and studied Byzantine art) and Josef Székely (1838-1901) (the photographer that made the first photo’s of Ohrid in 1863). I decided to bid & win first and research later.

The auction started. The “Skopje” drawing was scheduled toward the end of the catalogue. After a few hours, finally the object was offered for sale and I started with a modest bid. Then a surprise happened. An avalanche of biddings from all over the world. The price went 5 times above its opening value within 1 minute. “What is going on over here?”, I thought. The euphoria took me, I released all the breaks, and I continued to bid “all-in”. At the end I won, but I had to impose a serious savings restriction in the comings months to pay for this pleasure. The painting arrived from Budapest; it was prettier than on the photos. I started to research for János Vaszary.

—

János Miklós Vaszary (30 November 1867 – 19 April 1939) came from influential Hungarian family. His uncle was Kolos Ferenc Vaszary, the Archbishop of Esztergom. He studied art at prestigious fine art academies in Budapest, Munich and at the Julian Academy in Paris. From Paris, he brought a French impressionistic style that made him very successful in his time. During World War I, he served as a correspondent on the Serbian front and his imagery became more dramatic. Obviously, he was stationed in Skopje, and my search for his “Skopje” period brought me to the collection of the Hungarian National gallery, which hold a very unusual work of him: “Camel caravan in Skopje 1916” oil on canvas.

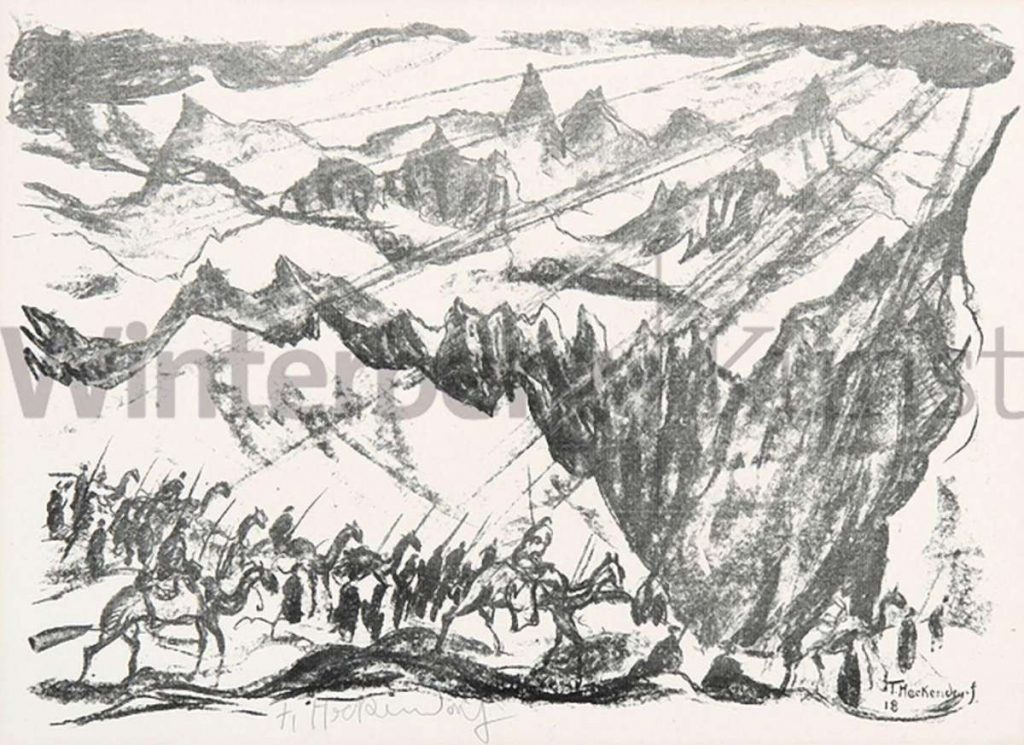

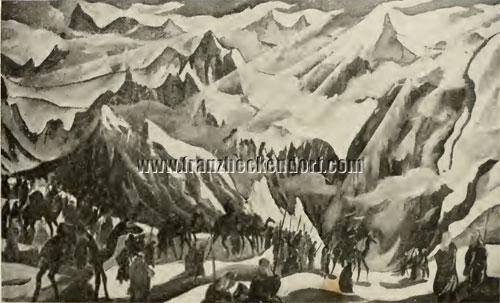

“Camels in Skopje in 1916? Bizarre, but….I have seen this somewhere before”, I thought. The camel scene brought my memories back to 2012 when I saw a lithography of the German painter Franz Heckendorf (1888-1962) entitled “Camels Caravan 1918” (Kamelkarawane).

—

Franz Heckendorf (1888-1962) was a German painter and one of the founders of the important modernist art group Berlin Secession. During the First World war he served in the German army in Macedonia in 1916 and 1917, and later in 1918 moved to Mesopotamia. Between 1943-45 he was arrested and convicted for helping his Jewish friends escape and was sent to the concentration camps Waldshut and Mаuthausen. He managed to survive and became professor at the Art academies in Vienna, Salzburg, and Munich.

At the time I discovered this lithography, I thought that this is a scene from Mesopotamia because of its “Camels” composition that I could not associate to Macedonia, and because if the year on the print: 1918. But the “Camel Caravan in Skopje” discovery made me to revisit this work and look more carefully.

Indeed, I overlooked an important detail. The lithography was made and published in 1918, when the war ended, BUT it was made after a small drawing from 1917 which made in Macedonia:

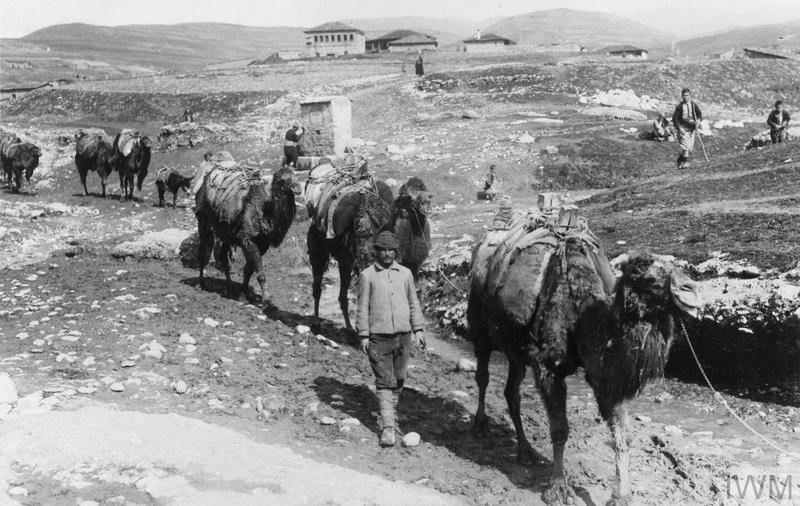

“So there were Camels in Macedonia in the Great War, but why and where?”. I continued to research. The research took me to the British Imperial War Museum in London.

—

The Imperial War Museum in London has two German photographs from 1917 showing that the Turkish army did used these animals for transport in the Great War. The animals were not brought to Macedonia to entertain the Macedonian shepherds and farmers. The real reason can be found in one testimonial of a British soldier from 1916 recorded in the British National Army Museum:

‘Marching is very hot and tiring and we get a thirst which no amount of drinking will satisfy; our water bottles are very precious things. Our bottles are filled before moving off and no man must drink until the order is given, although we get a longing to empty the bottle in one glorious drink. The water men have difficulty in keeping up the supply, which has to be carried in leather bags on the mules.

We go a long way up the Seres Road, one of the few decent roads in the country, then branch off… I begin to lose interest in life and when we lie down again would like to stay there and die, but there is some strange force which says “stick it” until you drop from sheer exhaustion… Through the endless night we put one foot in front of the other, aching in every joint’.

Diary of Private George Veasey, 8th Battalion The Oxfordshire

and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, July 1916

All soldiers on the Macedonian front faced a boiling summer climate and many succumbed to heatstroke. The British troops used mules and bicycles and travel was usually undertaken at night. Then, there was malaria epidemy, which killed during the Macedonia campaign 160 000 British soldiers alone. The roads in Macedonia were scarce, the military convoys were moving in unpaved terrains All these conditions made the use of camels more favorable than horses and mules. A camel can go up to 26 hours without water and can carry 2.5 times more load than a mule. Bactrian camels with two humps are significantly more resistant to viruses and bacteria than horses and mules.

The Turkish army has followed the tradition of the early Islamic Conquests, when the Arabs managed to take on both the Byzantine and Persian empires, simultaneously, and defeat both, drastically reducing the territory of the former, and completely destroying the latter. Camels played a big role, in that they allowed the Arabs to quickly mobilize and shift reinforcements and supplies from one theater of operations to the other, across difficult desert terrain that their opponents didn’t expect an attack from. And so, despite being greatly outnumbered, they managed to keep the initiative and stay on the offensive, exploiting their ability to quickly mass and concentrate their forces. The mobility afforded them by camels allowed them to pick and choose when to give battle if circumstances were favorable, and when to fade back into the desert when their enemies had the edge, only to reemerge somewhere else, hundreds of miles away, and launch an offensive from that direction. And in the meantime, the mobility of camels allowed them to send a slew of raiding parties into enemy territory, from all directions across their frontiers, constantly disrupting and sowing chaos in their enemies’ lands. So camels were excellent for strategic mobility.

Camels in warfare were not only used by Ottomans, but also by western civilizations. Napoleon employed a camel corps for his French campaign in Egypt and Syria. Americans planned to use camels in the Civil War. 34 camels were brought in the spring of 1856 to survey the wagon road from Albuquerque to Los Angeles, but the mule lobby in Missouri threw a hissy. “Camels,” they said, “were ill-tempered, smelly, stubborn and ugly. Worst of all they wouldn’t learn English.”. The camels were released in Arizona desert and they were wondering free over there. The last descendent of the original herd was captured in the wilds of Arizona in 1946.

During the late 19th and much of the 20th centuries, camel troops were used for desert policing and patrol work in the British, French, German, Spanish and Italian colonial armies.

In the Great War, the Turks were not the only one. The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East. The ICC became part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) and fought in several battles and engagements, in the Senussi Campaign, the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, and in the Arab Revolt. The brigade suffered 246 men killed. The ICC was disbanded in May 1919 after the end of the war.

—

The work on the Lexicon took me on many unexpected journeys like this one – from a discovery of a new artist name to the study of the use of the camels in military warfare. Such journeys are one of the greatest things in this project. You never know where the next discovered painter will take you.

Information and photos taken from:

- Hungarian National Gallery – Janos Vaszary – Camel Caravan in Skopje (https://en.mng.hu/artworks/camel-caravan-skopje/)

- Franz Heckendorf Camels Caravan 1918 litho: https://www.winterberg-kunst.info/

- Franz Heckendorf – Camels Caravan 1918 – detailed information: https://www.luederhniemeyer.com/franzheckendorf/29082_e.php

- Imperial War Museum, photos with Camels from Skopje 1917 : https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205330263

- British National Army Museum – the Macedonian Front: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/salonika-campaign

- Advantaged of camels : https://www.quora.com/What-were-the-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-camels-over-horses-in-medieval-warfare-Why-werent-they-more-popular

- Camels v.s mules in the wild west: https://truewestmagazine.com/camels-vs-mules-2/

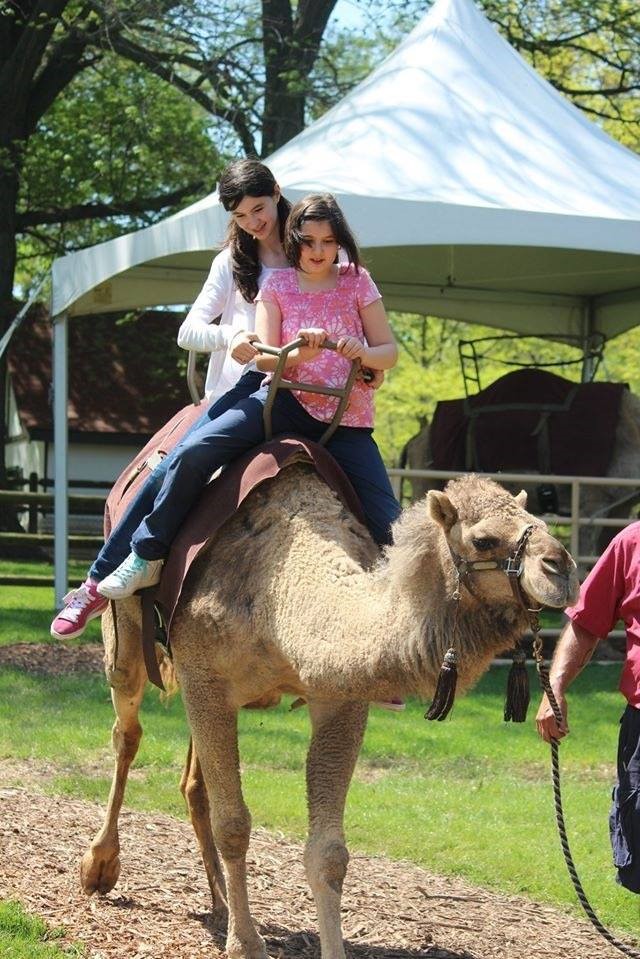

The origin of my camel obsession – Sara and Eva on a camel below, 2011.