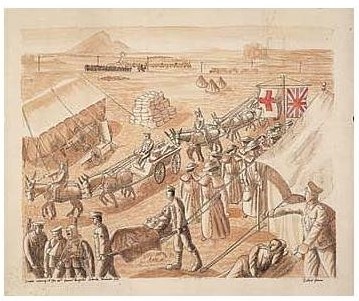

Imperial War Museum (IWM) London, 2018. The preparation for a large exhibition with a title “Lest We Forget” to commemorate 100 years from the end of the Great War is at full steam. The team of the exhibition curator Laura Clouting is selecting the most important World War One paintings from the museum depot in the basement and placing them to a prominent display on the fourth-floor gallery of the museum. One painting stands out with its beauty and symbolism. It’s by Sir Stanley Spencer (1891-1959) with the somewhat cumbersome but literal title: Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

Stanley Spencer served as a medical personnel in the 68th Field Ambulance in Macedonia during the war. Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing-Station at Smol shows a temporary operating theatre in an old Orthodox church in the village Smol, located 14 km south of Gevgelija. Spencer was deeply religious. ‘The wounded passed through the dressing stations in a never-ending stream, but I meant it not as a scene of horror but a scene of redemption‘. – he wrote later. “I felt there was a spiritual ascendancy over everything.“.

The center of the painting is an operation table where the doctor is trying to save the soldier lives. They are coming from everywhere, heavily wounded, dragged by the mules from the battlefield nearby. The operation room is illuminated as a symbol of the doors to Heaven. The doctor is St. Peter, the gatekeeper of the Heaven. Some soldier souls will go to Heaven, some will stay on Earth.

This religious symbolism will become a “trademark” of the art of Stanley Spencer. It will appear continuously in all his paintings. This style has roots in Spenser’s family tragedy which will haunt him through the rest of his life.

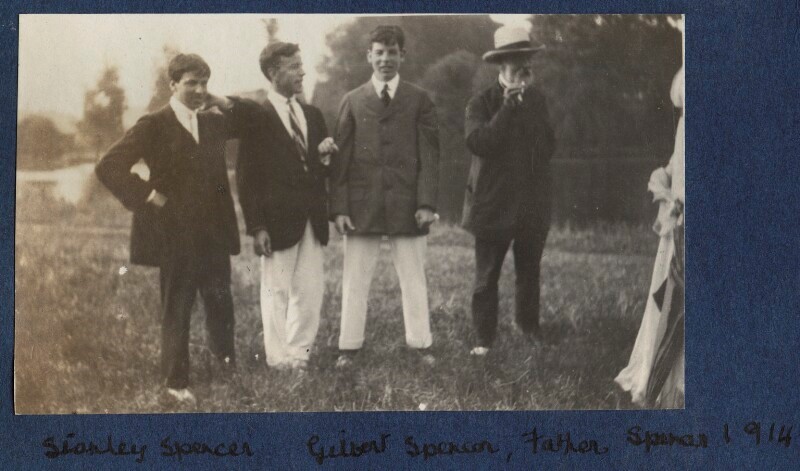

Cookham, Berkshire, 1912. Nicknamed as “a village in Heaven”, a picturesque Victorian village Cookham was favorite place for British aristocrats and artists at the end of the 19thy century. Noble families lived in that region, such as Lord Boston at Hedsor Lodge, the Duke of Westminster and later Waldorf Astor at Cliveden. At the turn of the century the Thames itself was the scene of social mêlée as the upper reaches became very fashionable for boating events. The Spencer family was well known in the village. The father William (1845-1928) who was a village vicar, organ player and music teacher and the mother Anna Caroline Slack (1854-1922) known as singer with a nickname “Birdie” had 9 children. With rather eccentric views on the society, they educated their children themselves at home. The principles of their education were: 1) Strong passion for art, 2) Spirituality and 3) Strive for perfection. The result was that all children became exceptional intellectuals with high artistic achievement. All of them were top musicians, painters or writers, but father’s demand for perfection took a toll on the children – the eldest son Will, a distinguished pianist and later music professor in Germany, had a nervous breakdown, and the eldest daughter Annie, a viol player, was institutionalized for her mental deterioration.

The three youngest boys were inseparable and called themselves “The Three Musketeers”.

The oldest “musketeer” is Sidney Spenser born in 1888, he graduated from Oxford university with aim to become a vicar and was skilled organ player. The middle “musketeer” is Stanley Spenser, born in 1891, and graduated from the Slade School of Art in 1912. He instantly became a respected contemporary art painter winning several prices and organized several exhibitions. The youngest “musketeer” was Gilbert Spencer, born 1892, who also studied art at Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts and the Royal College of Art and followed the footsteps of his brother Stanley at the Slade School of Art starting his studies there in 1913.

The future looked bright and the sky was the limit for the ambitious brothers. Then the World War One started.

London, 1914. The United Kingdom called its sons for a duty in the Great War. It was the moment to show a patriotism and bravery.

The father William and the mother Anna were strongly against the military service, but the children believed that it is a duty to serve.

The oldest “musketeer” Sidney joined Officers Training Corps while he was still in Oxford. Later he served as a Lieutenant in the Norfolk Regiment. He was appointed as a “Bombing and Gas Officer” and fitted 1500 men with gas masks shortly before finally persuading the War Office to agree to his demand to be allowed to serve in France. He wrote home “I am happy at last, I am no longer playing at soldiers, but feel at length I am a real soldier“.

To satisfy his parents, the youngest “musketeer” Gilbert enrolled himself for a non-combat service at the Royal Army Medical Corps in Bristol hospital. The middle “musketeer” Stanley wanted to protect his younger brother and he enrolled himself to the Royal Army Medical Corps in Bristol too. Gilbert did not want to be baby sited, so he tried to distance from Stanly by volunteering in an active military service and was transferred to the Macedonian front in Dojran. Stanley hated the war, he was physically small and thin, with a gentle health. But he could not leave his baby brother alone. He asked to be transferred to the Macedonian front too. In 1916 he was transferred to the Macedonian front as medical assistant in a field ambulance in the camp Chaushitsa (‘Corsica’ to the soldiers) in the Vardar Valley, 15 kilometers opposite the Bulgarian forces.

Smol, Macedonia, September 1916. Macedonian front extended more or less along the northern frontier of Greece.

It had been hastily organized in 1915 in order to deter the enemy central powers – Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Turkey – from violating the neutrality of Greece. An ad-hoc defensive force from several allied armies arrived in the port of Salonika to create a defensive screen along the frontier – British in the east around Salonika itself, French in the center, then Serbians, then Russians, then Italians in the west adjoining neutral Albania, the French being in overall command. The role of the Army of the Orient, as the French commander grandly called it, was essentially defensive. No-one in government, French or British, expected it to undertake a major offensive, especially after the disaster of Gallipoli. But from time to time commanders ordered local attacks, partly to keep up a so-called offensive spirit but also to improve defensive positions. One of these attacks awaited Stanley a few days after his arrival.

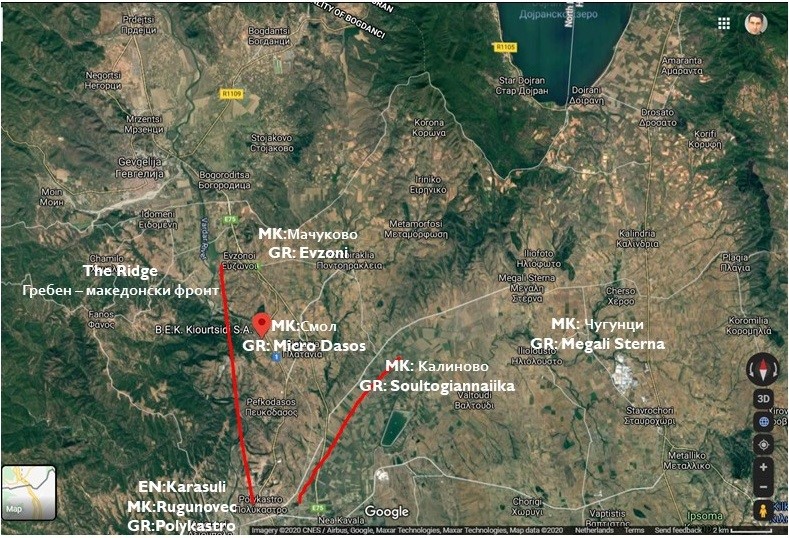

The British zone covered the country about thirty kilometers north of the port of Salonika, to the east of the River Vardar. It was divided by topography into a quieter eastern sector along the Struma river, and the more active western sector adjacent to the Vardar, whose valley acted as the boundary between the British and French armies, and was then, as now, the major highway into Greece. The British front line defending this highway stretched at right-angles to it for some fifteen kilometers along the northern-facing slopes of a ridge of high ground stretching east between the towns of Karasuli (in Macedonian: Rugunovec (Kara Sule) in Greek: Polykastro) near the Vardar and Kalinova (In Macedonian: Kalinovo, in Greek: Soultogiannaiika) near Lake Dojran. The slopes of the Karasuli-Kalinova ridge were in effect the last bastion before Salonika. Whoever controlled the ridge near the village of Machukovo (Greek: Evzoni). it controlled the pass toward Salonika. In September 1916, the ridge was controlled by the German army and there was a clear danger that the German-Bulgarian army may take over Salonika by storm. The British army got an order to take over the peak of the ridge known in French as ‘Piton des Mitrailleuses’ (‘Machine Gun Hill’ to the British.).

Gilbert Spenser arrived in Macedonia and was allocated in the 28th Field Hospital in Dodulari (Greek: Diavata) Thessaloniki. One of his drawings – arrival of medical sisters depicts his station

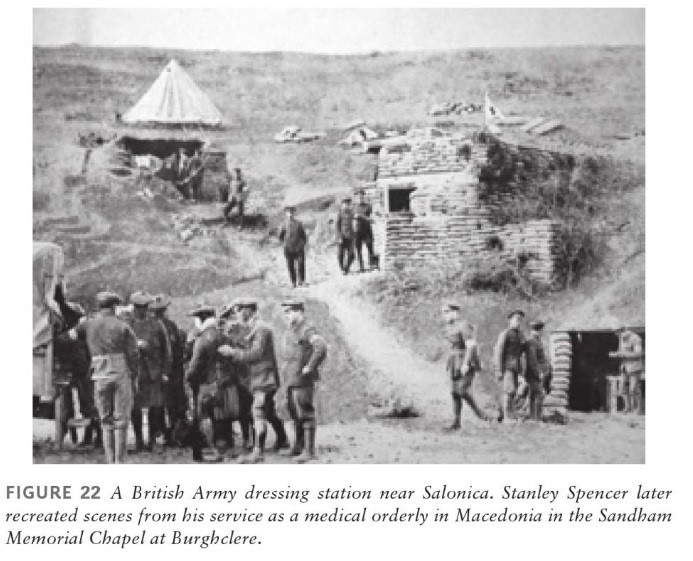

Stanley Spenser was allocated at first in Karasuli. The moonlit night of 13/14th September was chosen for the operation. To support the attack Stanley’s section of 68th Field Ambulance was moved west to the abandoned village of Smol (today Greek name is: Mikro Dassos) behind the Matchukovo front line. In Smol a dressing station had been set up in the village church which was destroyed during Balkan wars in 1912.

The “dressing station” was a medical middle station between the battleground at front and field ambulance in the back. The purpose of the dressing station was to stabilize the wounded and select which wounded soldiers can be saved, so that they are transferred to the ambulance first.

The Macedonian roads were scarce and rocky. Normally, the wounded would have been transferred with a horse or gasoline car. But in Macedonia, the only possible way was a transport with so called “travoys” – A stretches with one side tied to a mule, and the other side dragging on a ground. The sound of the dragging “travoys” was loud and unpleasant. Stanley Spenser will develop a phobia from scratching sound until the rest of his life.

The battle for the Machine Gun Hill near Evzoni/Machukovo started with artillery bombardment on 13th of September 1916. The bombardment took whole day. At 7:30 pm, The British assault battalion went out of the trenches and started a direct attack. The British attacked with their 12th Lancs Fusiliers and the 14th King’s Own protected on the left flank (the Vardar River flank) by 11th Royal Welch Fusiliers and on the right by 9th East Lancs. Opposing them were the German 59th Infantry Regiment, well entrenched and dug in, with 146th Infantry Regiment to its left and Bulgarian infantry battalions in reserve.

The British started to occupy part of the hill, and they were slowly climbing up. Around 2 am, the Machine Gun Hill had been captured.

The first travoys would thus have reached Smol about 9.0pm and have continued during the night under moonlight. This must have been the period of Stanley’s painting.

German reaction in the form of shelling and counterattacks was furious. During the morning of the next day, 14th September, the British held on grimly to their captured positions. Then, about noon, the Germans changed tactics. Bringing in Bulgarian battalions as reinforcements, they attacked the right flank. One by one the pockets were overwhelmed. By mid-afternoon the battalions on the hilltop were exposed not only to the front, but also to the flank. There was no point in trying to hold on. The order to withdraw was given, and by 4.30pm all the British battalions were back in their original trenches. The British losses – killed, wounded, or captured – numbered 586.

The status quo resumed. Nevertheless, the efforts of the allied soldiers were not in vain. Greece was not invaded, and its government under Venizelos, (although the King favored the

the Germans), remained grateful for the allied intervention.

Today, At the highest point of the Karasuli-Kalinova Ridge where it overlooks the Vardar Valley, there is national monument for all fallen British soldiers from this battle. The busts are of the allied war leaders.

Thessaloniki, September 1918. The Great war was coming to its end. Raised to strive for perfection, The Spenser brothers tried to be perfect soldiers too. On the French front, the oldest “musketeer” Sidney was wounded in August 1918 during the Battle for Amiens, He was awarded the Military Cross for his bravery. The youngest “musketeer” Gilbert left the Macedonian front and moved to a hospital ships in the Mediterranean, and then to North Africa for the duration of the war. The middle “musketeer” Sidney wanted to be a soldier too. He tried to move from medical units to infantry several times, but he got sick from malaria and bronchitis and got hospitalized. He was transferred to 143rd Field Hospital in Todorovo near Dojran Front, where he drew sketches from the daily lives of the British soldiers.

During one Bulgarian attack in April 1917, Stanley lost his drawing kitbag with all his drawings and paintings. He enrolled himself as an infantry soldier to the 7th Royal Berkshire Regiment, but he did not engage in battles. Instead, as a non -alcoholic, he was distributing beer rations to the soldiers.

Finally, his moment to leave a personal mark on the Great War came in May 1918, when the British War Memorials Committee commissioned him to produce an image of a service at the front. Stanley started to sketch the night at Smol dressing station from its memory.

Then the bad news came.

On 24th September 1918 the oldest “musketeer” Sidney Spenser was killed in action while his Regiment tried to retake the small French village Epehy, near Belgian border. He was one of the 998 British victims fallen in the Battle of Epehy and buried nearby in the local cemetery.

Cookham, Berkshire January 1919. The Great War ended on 11th November 1918, just over a months since the death of the beloved brother Sidney. Stanley Spenser is back home in Cookham and he started to work on the commissioned painting of Smol Macedonia. He is devastated from the loss of his brother. Being deeply spiritual, he tries to find reconciliation and accept God’s will. The Dressing Station painting started to drift from reality and embed religious symbolisms. The light in the middle of the church is Life, the darkness of the hills of Macedonia in the corner of the painting are Death. The mules with their travoys are bringing soldier soul into the center of the painting, like the souls going to the gates of Heaven. Despite the bloody battle nearby, there is a peace in the faces of the wounded soldiers. They reconcile with their destiny.

The painting was like no other British war painting. It is intimate and deep, with many layers of symbolism. But the audience in 1918 was looking for more heroic and straightforward. In December 1919, the painting joined others in the major Exhibition of The Nation’s War Paintings at Burlington House (the Royal Academy.). The critics were polite, but not impressed. It will take a decade until the art critics realized that “Smol, Dressing Station” painting is the most remarkable work of art of the British war painting.

Stanley Spenser was disappointed from reception. He wants the art lovers to recognize and endorse his pain from the loss of his brother. He started his next project, more grandiose than “Smol”: a massive 3 x 5 meter canvas with title: “The Resurrection, Cookham”

For Spencer, being a devout Christian. Cookham, was a place full of mystical significance. The Christian New Testament describes how, at the end the world, everyone who has ever existed will be brought back to life. Spencer makes his local churchyard the setting for this resurrection of the dead. He depicts biblical figures alongside people he knew in the scene, including his wife and his nude self-portrait in the center of the painting. The hills in the back are hills of Kalinovo, Macedonia. Stanley Spencer lounges to see his brother again, back from the dead from the Great War. ‘It gave me the feeling that the resurrection was a peaceful occasion and I’m fond of peace and I like the happiness – that was the main idea of this picture.’ – Stanley Spencer will say during one of his interviews.

The London art critics were euphoric. The painting was a smashing success. Stanley Spencer was proclaimed as one of the most important British modern painters. The critics also revisited “Smol, Macedonia 1916” painting and started to understand and value the symbolism there.

But the pain of the lost brother is still there. The reconciliation is not complete.

Stanley Spenser is still looking for an internal peace. He starts his next project, even more grandiose – “Resurrection of Soldiers, 1927-1932 decoration of a chapel in Sandham which occupies the entire six meters by five meters wall above the altar.

Officially , the altar of the chapel is dedicated to Stanley Spencer’s friend – fallen soldier lieutenant Harry Sandam, who died in the Battle of Salonika. But Spenser gives tribute to all fallen soldiers, but outmost, to his brother.

A dull gray and brown Macedonian battlefield landscape takes up the majority of the mural. At the base of the painting soldiers emerge from the ground and grasp the white crosses that are ubiquitous symbols of the mortal carnage of the First World War. Naturally, guided by the triangular composition of the paintings, one’s eye travels up this painting: one observes the soldiers clasping hands in greeting and watches the soldiers walking upwards past revivified horses and handing their crosses to Jesus, who is placed at the apex of the triangle. The success of this painting is in its monumental perspective: it submerges the viewer’s consciousness utterly and, for the time you stand in front of it, these men really rise again.

On the opposite walla, Spencer recreates Macedonia – he paints the military camp in Karasouli and the daily scenes of soldier lives.

The altar was finished in 1932, and it was instantly proclaimed by the British art critics as Britain’s Sistine Chapel.

The altar is Stanley’s crescendo, his last goodbye to brother Sidney and his final act of reconciliation with the pain. As art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon said: “This is not so much a war memorial as an amelioration of war in art. The Resurrection of the Soldiers, showing a throng of bodies pressing up out of their graves, was Spencer’s way of digging up the cemeteries of northern France, at least in his imagination, and bringing the young bodies of a dead generation back to life again.” In art, he shows that anything is possible, time can be rewound, and reality effaced. In the picture, Spencer could live in the imaginary perfect world that he so longed for”.

These three works are considered as the best art that Stanley Spenser created in his career.

THE AFTERMATH

As a result of postwar events, Turkish populations long settled in Greece were repatriated in an exchange with Greeks uprooted by the Turks from Asia Minor. Greek refugee families from the devastated Smyrna (Izmir) settled in Smol village in 1923. Names, of course, have since changed. Salonika is now Thessaloniki, the River Vardar is now the Axios, Karasuli is now Polikastro, Chidemli (Macedonian: Hidemli) is now Metamorfosis, Machukovo is Evzoni, and Smol is part of Mikro Dasos (‘Small Forest’) although its older name (Smol or Smoli) is still recognized locally.

In 1925 Stanley Spenser married Hilda Carline, who was a girlfriend of his younger brother Gilbert. They had two children and harmonious marriage. Then in 1932 he met Patricia Preece, an aspiring artist who lived in the village with her close friend, another, more talented artist called Dorothy Hepworth. She was an exotic creature who entranced Stanley. He loved to take her to the large department store in Maidenhead and buy her jewels and furs. She became a model for several of his paintings and eventually his relationship with her led to his divorce from Hilda.

In 1937 – Stanley Spenser divorced his wife Hilda Carline and only four days after he married Patricia Preece. The marriage was an immediate failure, because Patricia and her friend Dorothy had a lesbian relationship. Patricia and Dorothy left for the honeymoon in St Ives together. Today Patricia Preece would be called ‘high maintenance’ and Stanley paid her considerable expenses until the day he died. Together with his responsibility for his family, and his lack of any ability to manage his own finances Spencer needed to keep painting to earn money, and his agent Dudley Tooth persuaded him to paint ‘anything that would sell’.

He died in 1959 and during his lifetime he was awarded the CBE and knighted and had been elected to the Royal Academy. Hilda remained the love of his life, and he continued to write to even after her death. He was a most sociable character with many friends and supporters who has been called eccentric and Patricia in her diaries even called him ‘mad’. He was also undoubtedly one of our greatest British artists.

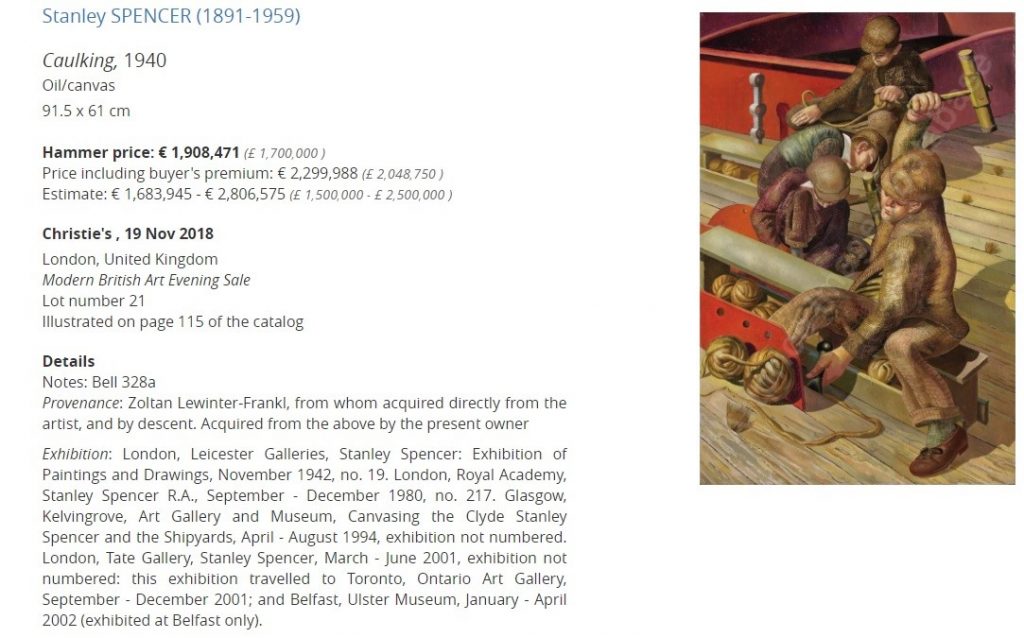

On 19 November 2018, the auction house Christie’s London sold a painting of Stanley Spenser for one million and 700 thousand British pounds. The value and the demand of the paintings of Stanley Spenser continues to rise.

Information and photos sources:

- Photos of Spencer brothers 1914: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/

- Imperial War Museum, Dressing Station painting: https://www.iwm.org.uk/

- Information on Sidney Spencer (1888-1918): http://www.rbwm.gov.uk

- IWM 4th floor exhibition

- https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/

- Stanley Spencer Gallery : https://stanleyspencer.org.uk

- Lest we forget exhibition: https://www.iwm.org.uk

- Spencer Family and Cookham: http://www.gilbertspencer.org/

- Spencer in Macedonia: http://www.stanleyspencer.co.uk/travoys.htm

- Map of Macedonian Front: http://www.levantineheritage.com

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

- Macedonian topographic names: https://makedonija.name/history/

- Ressurection o Cookham: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/

- Ressurection: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/

- Ressurection: https://m.theartstory.org/artist